J Inflamm Res

. 2015 Mar 24;8:83–96. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S69656

The effects of grounding (earthing) on inflammation, the immune response, wound healing, and prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases

James L Oschman 1, Gaétan Chevalier 2,?, Richard Brown 3

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC4378297 PMID: 25848315

Abstract

Multi-disciplinary research has revealed that electrically conductive contact of the human body with the surface of the Earth (grounding or earthing) produces intriguing effects on physiology and health. Such effects relate to inflammation, immune responses, wound healing, and prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. The purpose of this report is two-fold: to 1) inform researchers about what appears to be a new perspective to the study of inflammation, and 2) alert researchers that the length of time and degree (resistance to ground) of grounding of experimental animals is an important but usually overlooked factor that can influence outcomes of studies of inflammation, wound healing, and tumorigenesis. Specifically, grounding an organism produces measurable differences in the concentrations of white blood cells, cytokines, and other molecules involved in the inflammatory response. We present several hypotheses to explain observed effects, based on current research results and our understanding of the electronic aspects of cell and tissue physiology, cell biology, biophysics, and biochemistry. An experimental injury to muscles, known as delayed onset muscle soreness, has been used to monitor the immune response under grounded versus ungrounded conditions. Grounding reduces pain and alters the numbers of circulating neutrophils and lymphocytes, and also affects various circulating chemical factors related to inflammation.

Keywords: chronic inflammation, immune system, wound repair, white blood cells, macrophages, autoimmune disorders, The effects of grounding (earthing) on wound healing

Introduction – The effects of grounding (earthing) on wound healing

Grounding or earthing refers to direct skin contact with the surface of the Earth, such as with bare feet or hands, or with various grounding systems. Subjective reports that walking barefoot on the Earth enhances health and provides feelings of well-being can be found in the literature and practices of diverse cultures from around the world.1 For a variety of reasons, many individuals are reluctant to walk outside barefoot, unless they are on holiday at the beach. Experience and measurements show that sustained contact with the Earth yields sustained benefits. Various grounding systems are available that enable frequent contact with the Earth, such as while sleeping, sitting at a computer, or walking outdoors. These are simple conductive systems in the form of sheets, mats, wrist or ankle bands, adhesive patches that can be used inside the home or office, and footwear. These applications are connected to the Earth via a cord inserted into a grounded wall outlet or attached to a ground rod placed in the soil outside below a window. For the footwear applications, a conductive plug is positioned in the shoe sole at the ball of the foot, under the metatarsals, at the acupuncture point known as Kidney 1. From a practical standpoint, these methods offer a convenient and routine, user-friendly approach to grounding or earthing. They can also be used in clinical situations, as will be described in the section entitled Summary of findings to date.1

Recently, a group of about a dozen researchers (including the authors of this paper) has been studying the physiological effects of grounding from a variety of perspectives. This research has led to more than a dozen studies published in peer-reviewed journals. While most of these pilot studies involved relatively few subjects, taken together, the research has opened a new and promising frontier in inflammation research, with broad implications for prevention and public health. The findings merit consideration by the inflammation research community, which has the means to verify, refute, or clarify the interpretations we have made thus far.

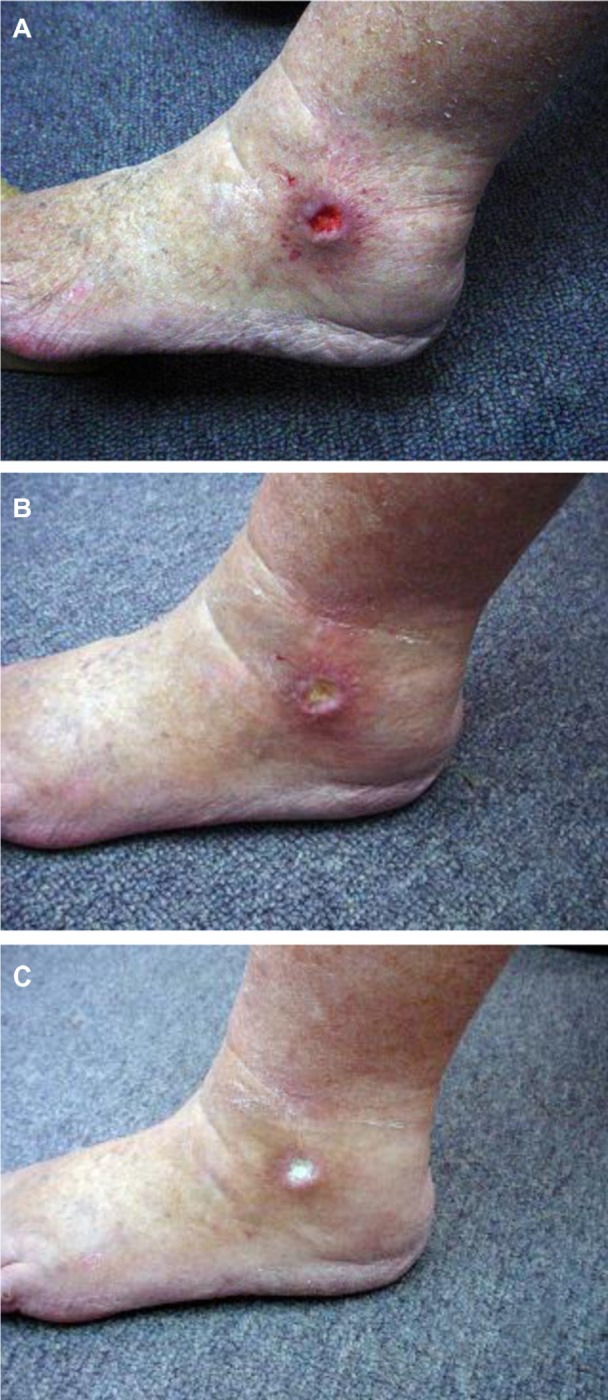

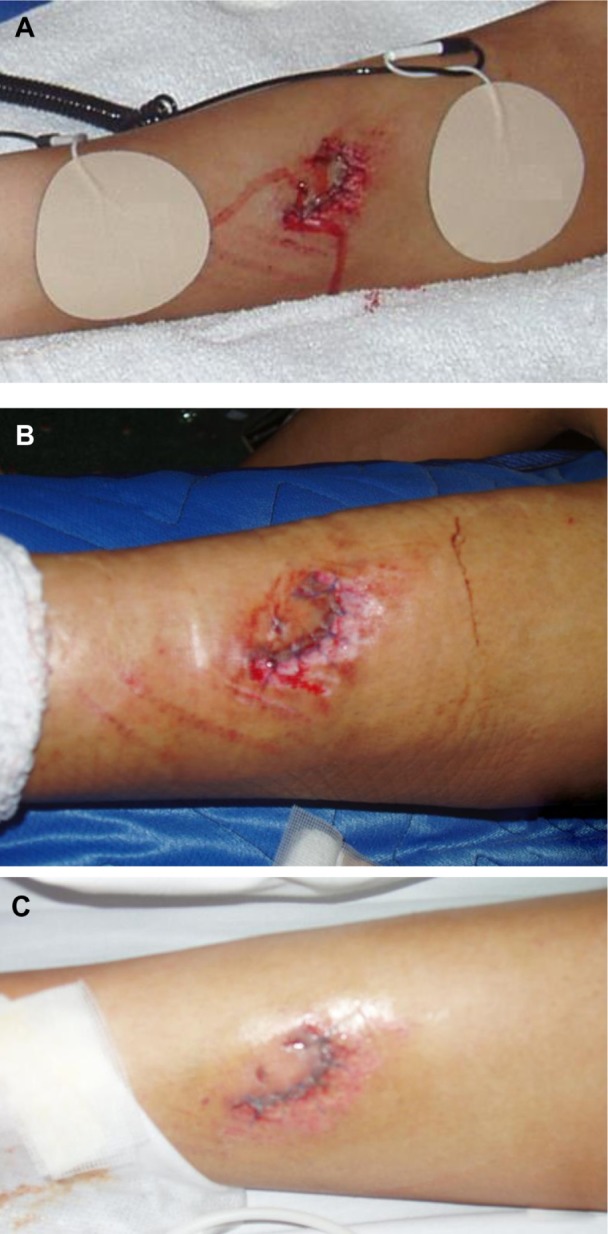

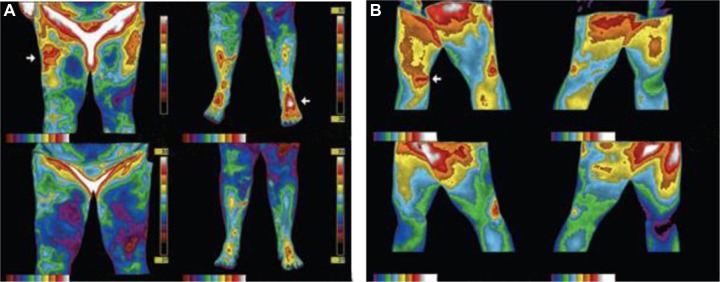

Grounding reduces or even prevents the cardinal signs of inflammation following injury: redness, heat, swelling, pain, and loss of function (Figures 1 and 2). Rapid resolution of painful chronic inflammation was confirmed in 20 case studies using medical infrared imaging (Figure 3).2,3

Our main hypothesis is that connecting the body to the Earth enables free electrons from the Earth’s surface to spread over and into the body, where they can have antioxidant effects. Specifically, we suggest that mobile electrons create an antioxidant microenvironment around the injury repair field, slowing or preventing reactive oxygen species (ROS) delivered by the oxidative burst from causing “collateral damage” to healthy tissue, and preventing or reducing the formation of the so-called “inflammatory barricade”. We also hypothesize that electrons from the Earth can prevent or resolve so-called “silent” or “smoldering” inflammation. If verified, these concepts may help us better understand and research the inflammatory response and wound healing, and develop new information on how the immune system functions in health and disease.

The effects of grounding (earthing) on wound healing

Conclusion – FULL ARTICLE HERE

Accumulating experiences and research on earthing, or grounding, point to the emergence of a simple, natural, and accessible health strategy against chronic inflammation, warranting the serious attention of clinicians and researchers. The living matrix (or ground regulation or tissue tensegrity-matrix system), the very fabric of the body, appears to serve as one of our primary antioxidant defense systems. As this report explains, it is a system requiring occasional recharging by conductive contact with the Earth’s surface – the “battery” for all planetary life – to be optimally effective.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Martin Zucker for very valuable comments on the manuscript. A Clinton Ober of EarthFx Inc. has provided continuous support and encouragement for the research that has been done to explore the science of earthing, with particular focus on the immune system.

Footnotes

Disclosure

G Chevalier and JL Oschman are independent contractors for EarthFx Inc., the company sponsoring earthing research, and own a small percentage of shares in the company. Richard Brown is an independent contractor for EarthFx Inc., the company sponsoring earthing research. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ober CA, Sinatra ST, Zucker M. Earthing: The Most Important Health Discovery Ever? 2nd. Laguna Beach: Basic Health Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amalu W. Medical thermography case studies. Clinical earthing application in 20 case studies [undated article on the Internet] [Accessed July 5, 2008]. Available from: http://74.63.154.231/here/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Amalu_thermographic_case_studies_2004.pdf.

- 3.Oschman JL. Can Electrons act as antioxidants? A review and commentary. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:955–967. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevalier G, Sinatra ST, Oschman JL, Sokal K, Sokal P. Review article: Earthing: health implications of reconnecting the human body to the Earth’s surface electrons. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:291541. doi: 10.1155/2012/291541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaly M, Teplitz D. The biologic effects of grounding the human body during sleep as measured by cortisol levels and subjective reporting of sleep, pain, and stress. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(5):767–776. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):5995–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118355109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown D, Chevalier G, Hill M. Pilot study on the effect of grounding on delayed-onset muscle soreness. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(3):265–273. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterfield TA, Best TM, Merrick MA. The dual roles of neutrophils and macrophages in inflammation: a critical balance between tissue damage and repair. J Athl Train. 2006;41(4):457–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takmakidis SP, Kokkinidis EA, Similios I, Douda H. The effects of ibuprofen on delayed onset muscle soreness and muscular performance after eccentric exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(1):53–59. doi: 10.1519/1533-4287(2003)017<0053:teoiod>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Close GL, Ashton T, Cable T, Doran D, MacLaren DP. Eccentric exercise, isokinetic muscle torque and delayed onset muscle soreness: the role of reactive oxygen species. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(5–6):615–621. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-1012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIntyre DL, Reid WD, Lyster DM, Szasz IJ, McKenzie DC. Presence of WBC, decreased strength, and delayed soreness in muscle after eccentric exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;80(3):1006–1013. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.3.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franklin ME, Currier D, Franklin RC. The effect of one session of muscle soreness inducing weight lifting exercise on WBC count, serum creatine kinase, and plasma volume. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1991;13(6):316–321. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1991.13.6.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:64–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacIntyre DL, Reid WD, McKenzie DC. Delayed muscle soreness: the inflammatory response to muscle injury and its clinical implications. Sports Med. 1995;20(1):24–40. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199520010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith LL, Bond JA, Holbert D, et al. Differential white cell count after two bouts of downhill running. Int J Sports Med. 1998;19(6):432–437. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LL.Cytokine hypothesis of overtraining: a physiological adaptation to excessive stress? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000322317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ascensão A, Rebello A, Oliveira E, Marques F, Pereira L, Magalhães J. Biochemical impact of a soccer match: analysis of oxidative stress and muscle damage throughout recovery. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(10–11):841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith LL, McCammon M, Smith S, Chamness M, Israel RG, O’Brien KF. White blood cell response to uphill walking and downhill jogging at similar metabolic loads. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1989;58(8):833–837. doi: 10.1007/BF02332215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadbent S, Rousseau JJ, Thorp RM, Choate SL, Jackson FS, Rowlands DS. Vibration therapy reduces plasma IL6 and muscle soreness after downhill running. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(12):888–894. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gleeson M, Almey J, Brooks S, Cave R, Lewis A, Griffiths H. Haematological and acute-phase responses associated with delayed-onset muscle soreness. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1995;71(2–3):137–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00854970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(2):R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Clement D, Taunton J. The efficacy of Farabloc, an electromagnetic shield, in attenuating delayed-onset muscle soreness. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10(1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oschman JL. Charge transfer in the living matrix. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;13(3):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best TM, Hunter KD. Muscle injury and repair. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 2000;11(2):251–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selye H. The Stress of Life. Revised. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motoyama H. Measurements of Ki energy: Diagnoses and Treatments. Tokyo: Human Science Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colbert AP, Yun J, Larsen A, Edinger T, Gregory WL, Thong T. Skin impedance measurements for acupuncture research: development of a continuous recording system. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2008;5(4):443–450. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichmanis M, Marino AA, Becker RO. Electrical correlates of acupuncture points. IEEETrans Biomed Eng. 1975;22(6):533–535. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1975.324477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sokal K, Sokal P. Earthing the human organism influences bioelectrical processes. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(3):229–234. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selye H. On the mechanism through which hydrocortisone affects the resistance of tissues to injury; an experimental study with the granuloma pouch technique. JAMA. 1953;152(13):1207–1213. doi: 10.1001/jama.1953.63690130001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oschman JL, Oschman NH. Matter, energy, and the living matrix. Rolf Lines. 1993;21(3):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pischinger A. The Extracellular Matrix and Ground Regulation: Basis for a Holistic Biological Medicine. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heine H. Lehrbuch der biologischen Medizin. Grundregulation und Extrazellulare Matrix. [Handbook of Biological Medicine. The extracellular matrix and ground regulation] Stuttgart: Hippokrates Verlag; 2007. German. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pienta KJ, Coffey DS. Cellular harmonic information transfer through a tissue tensegrity-matrix system. Med Hypotheses. 1991;34(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(91)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szent-Györgyi A. Towards a new biochemistry? Science. 1941;93:609–611. doi: 10.1126/science.93.2426.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szent-Györgyi A. The study of energy levels in biochemistry. Nature. 1941;148(3745):157–159. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokita Y. Proteins as semiconductor devices [article on the Internet] Available from: http://www.jsst.jp/e/JSST2012/extended_abstract/pdf/16.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2014.

- 38.Sarpeshkar R. Ultra Low Power Bioelectronics. Fundamentals, Biomedical Applications, and Bio-inspired Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hush NS. An overview of the first half-century of molecular electronics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1006:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1292.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mentovich E, Belgorodsky B, Gozin M, Richter S, Cohen H. Doped biomolecules in miniaturized electric junctions. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(20):8468–8473. doi: 10.1021/ja211790u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuevas JC, Scheer E. Molecular Electronics: An Introduction to Theory and Experiment. Vol. 1. World Scientific Publishing Co; Singapore: 2010. (Singapore; World Scientific Series in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reimers JR, United Engineering Foundation (US) et al. Molecular electronics III. Vol. 1006. New York, NY: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joachim C, Ratner MA. Molecular electronics: Some views on transport junctions and beyond. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(25):8801–8808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500075102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heine H. Homotoxicology and Ground Regulation System (GRS) Baden-Baden: Aurelia-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chevalier G. Changes in pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood oxygenation, perfusion index, skin conductance, and their variability induced during and after grounding human subjects for 40 minutes. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(1):81–87. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miwa S, Beckman KB, Muller FL, editors. Oxidative Stress in Aging: From Model Systems to Human Diseases. Totowa: Humana Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oschman JL. Mitochondria and cellular aging. In: Klatz R, Goldman R, editors. Anti-Aging Therapeutics. XI. Chicago: American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine; 2008. 2009. pp. 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kessler WD, Oschman JL. Counteracting aging with basic physics. In: Klatz R, Goldman R, editors. Anti-Aging Therapeutics. XI. Chicago: American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine; 2009. pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stocker R. Antioxidant activities of bile pigments. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6(5):841–849. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paschalis V, Nikolaidis MG, Fatouros IG, et al. Uniform and prolonged changes in blood oxidative stress after muscle-damaging exercise. In Vivo. 2007;21(5):877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikolaidis MG, Paschalis V, Giakas G, et al. Decreased blood oxidative stress after repeated muscle damaging exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(7):1080–1089. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31804ca10c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Florczyk UM, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Biliverdin reductase: new features of an old enzyme and its potential therapeutic significance. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(1):38–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sedlak TW, Salehb M, Higginson DS, Paul BD, Juluri KR, Snyder SH. Bilirubin and glutathione have complementary antioxidant and cytoprotective roles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(13):5171–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813132106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Close GL, Ashton T, McArdle A, MacLaren DP. The emerging role of free radicals in delayed onset muscle soreness and contraction-induced muscle injury. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2005;142(3):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirose L, Nosaka K, Newton M, et al. Changes in inflammatory mediators following eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2004;10:75–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartmann U, Mester J. Training and overtraining markers in selected sport events. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(1):209–215. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCully KK, Argov Z, Boden BP, Brown RL, Bank WJ, Chance B. Detection of muscle injury in humans with 31-P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11(3):212–216. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCully KK, Posner J. Measuring exercise-induced adaptations and injury with magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(S1):S147–S149. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCully KK, Shellock FG, Bank WJ, Posner JD. The use of nuclear magnetic resonance to evaluate muscle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(5):537–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zehnder M, Muelli M, Buchli R, Kuehne G, Boutellier U. Further glycogen decrease during early recovery after eccentric exercise despite a high carbohydrate intake. Eur J Nutr. 2004;43(3):148–159. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swartz K. Health Care Cost Monitor. The Hastings Center; 2011. [Accessed January 18, 2011]. Projected Costs of Chronic Diseases. Available from: http://healthcare-costmonitor.thehastingscenter.org/kimberlySwartz/projected-costs-of-chronic-diseases/ [Google Scholar]

- 62.Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease. [Accessed January 18, 2011]. Available from: http://www.fightchronicdisease.org/issues/about.cfm.

- 63.Mac Kenzie WF, Garner FM. Comparison of neoplasms in six sources of rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;50(5):1243–1257. doi: 10.1093/jnci/50.5.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oschman JL. In: Mitochondria and cellular aging. Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XI. Klatz R, Goldman R, editors. Chicago IL: American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine; 2008. pp. 285–287. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Biagi E, Candela M, Fairweather-Tait S, Franceschi C, Brigidi P. Aging of the human metaorganism: the microbial counterpart. Age (Dordr) 2012;34(1):247–267. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee RP. Interface. Mechanisms of Spirit in Osteopathy. Portland, OR: Stillness Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Articles from Journal of Inflammation Research are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

ACTIONS

- View on publisher site

- PDF (3.6 MB)

- Cite

- Collections

- Permalink

RESOURCES

Similar articles

Cited by other articles

Links to NCBI Databases

On this page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Summary of findings to date

- Anatomical and biophysical aspects

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Footnotes

- References

Follow NCBI

NCBI on X (formerly known as Twitter)NCBI on FacebookNCBI on LinkedInNCBI on GitHubNCBI RSS feed

Connect with NLM

NLM on X (formerly known as Twitter)NLM on FacebookNLM on YouTube

National Library of Medicine

8600 Rockville Pike

Bethesda, MD 20894